|

| The Milgram experiments |

A few days ago, I listened to Radiolab's podcast "The Bad Show." It explored bad behavior in a couple of different ways. The segment that stuck with me was their take on the famous Milgram experiments on the lengths people will go to follow directions.

First, the context. An fake experiment on using electric shocks as a motivator for learning is staged. A regular citizen is brought and instructed by an administrator to give increasingly high shocks to a "learner" (actually a voice actor on a recording) if that person incorrectly answers parts of a memorization exercise. The "learner" purposefully starts making mistakes, forcing the regular citizen to decide to administer the shocks.

The real experiment is to see when the person administering the shocks stops the experiments. That person is forced to hear the "learner" scream in pain and beg to stop. Labels on the "machine" show that the person is administering deadly shocks to the learner.

The experiments were spurred by examining the idea: "How could so many German citizens be cogs in the Final Solution?" Nowadays, the experiments have been applied to subsequent genocides and also cover territory like: "How could so many Enron employees participate in a massive fraud?"

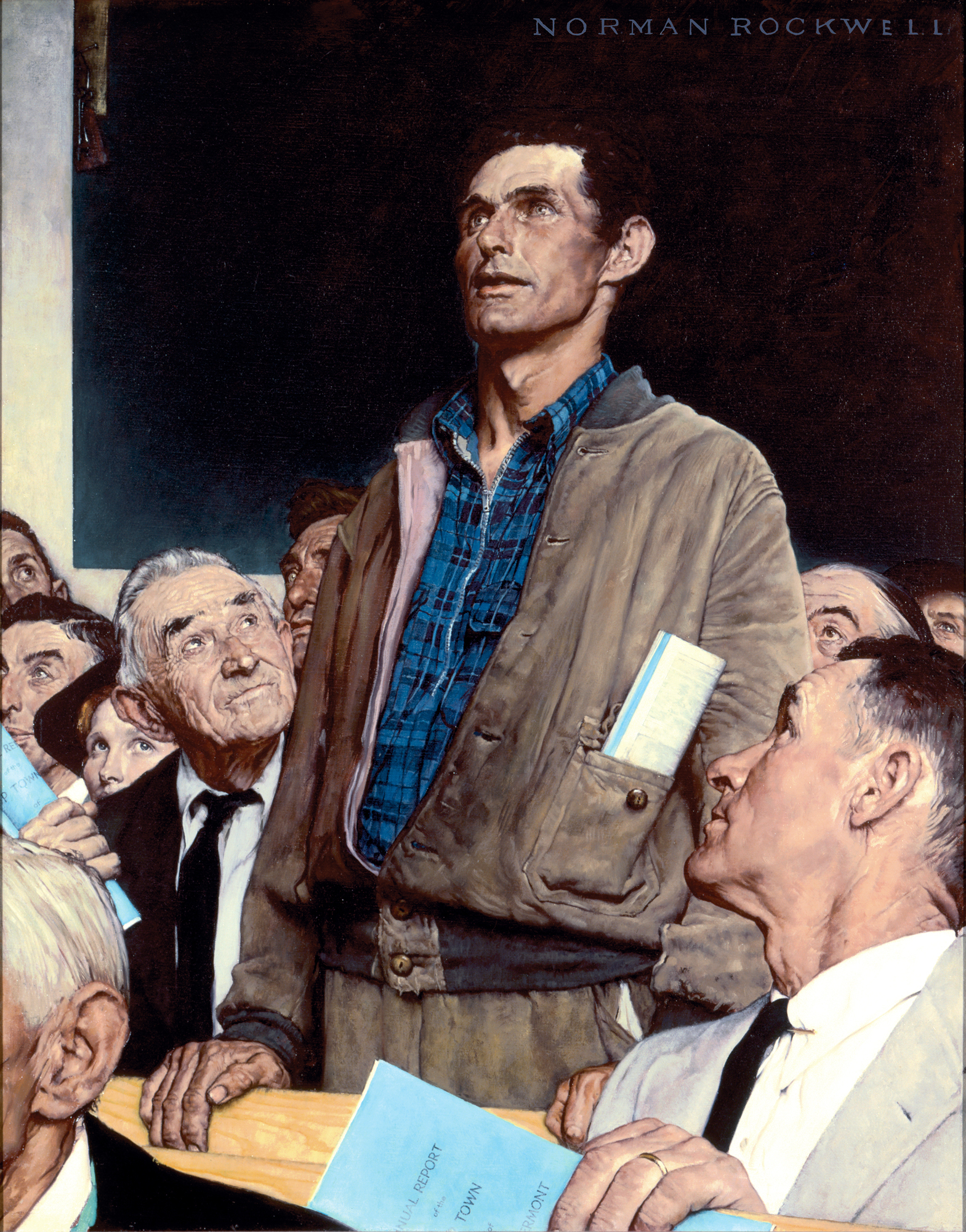

The headline of the experiment is that a disturbingly high percentage of people will basically do what they're told by a person in authority -- or even one who looks like she or he is in authority.

Milgram conducted dozens of variations of the experiment. Did it make a different in what the "administrator" was wearing? What about the age of the person giving instructions? What happens if the administrator gives rationale? What about if the administrator issues an order? What "The Bad Show" discusses are two important, oft-overlooked subtleties in the findings:

1) What got the highest rates of compliance was when the administrator justified the experiment in terms of contributing the greater good. If the citizens thought they were doing their part to advance the science of learning, around two-thirds of them were willing to shock the learner enough to kill them.

2) Giving direct orders was the least successful way of gaining compliance in killing people. About two-thirds of all citizens rebelled when giving a direct order to keep sending deadly shocks.

***

The implications of these results are exciting and horrifying. One could take them in a dozen different directions. For example, I couldn't help but see echoes of them in the Maryland football scandal where a coach inadvertantly ordered a player to exercise himself to death.

For today though, I want to focus on way the experiments' implications could be used in a positive way -- managing people, specifically students. (Writing this blog has a way of quickly exposing the limits of my lived experience.) In a way, me learning how to lead a classroom more or less confirmed Milgram's results.

When I was a rookie teacher, one of the benchmarks that I set for myself was being able to give an behavior instruction with no rationale and get compliance from the students. An order, basically.

I'm not sure how or why I got in my head that being able to order kids around was a mark of a teacher with a well-managed classroom. Then again, a lot of my ideas back then of what made for a good teaching were 100 percent wrong. I was always able to get a few to comply, but enough would rebel that in short order the lesson would go off the rails.

I never got to the point of being able to consistently, successfully order kids around. This is because as I got better at my job, I realized I didn't need to do it.

It's sort of similar to the famous photo of cyclists smoking cigarettes while riding in the first few Tour de Frances. Turns out smoking cigarettes is counter-productive if one is riding 100 miles a day! Also counter-productive: barking orders at adolescents.

|

| Not a successful racing strategy |

What I learned from much better teachers is that well-managed classrooms have a rationale -- implicit or explicit -- for everything that happens in executing a lesson. The teacher has set things up so the class doesn't need to rely solely on the authority of an adult for it to function. This creates a virtuous cycle where the teacher can achieve maximum compliance with a light touch. The students trust the teacher's direction, therefore the teacher can do all sorts of other things -- give suggestions, solicit peer feedback, restating rationale, clarifying or simplifying directions -- instead of issuing a series of orders (with explicit or implicit negative consequences) to achieve the day's goal.

Great leaders get the behavior they want by investing people in a clear vision, giving simple directions, depending more on persuasion than authority, and setting up strong systems to create a culture where people want to be best their best selves. If you observe one of these classes (or team or working groups), then you'll notice something interesting when there's off-task behavior. The person or people doing the non-compliant behaviors quickly give up because it's exhausting -- like swimming against the tide.

Thanks to Milgram, we better understand the power -- for good and for ill -- of investing people in a grand vision. The experiments showed that we are hard-wired to follow directions more often than not when we believe we a part of something big and great. It also illustrates the power and perils of being the person in charge. These are morally neutral observations.

What is up to us is our awareness of what we're asked to do and conversely, what we're asking of others when we lead.

The difference between knowing we humans have a tendency versus treating behavior as fait accompli is what makes a moral choice so hard in the first place.